An account of the ‘birth’ and initial problems of the TZ1 appeared in the March 1992 issue of Autocapital magazine – it can be read here.

Tuesday, March 1, 2022

Alfa Romeo TZ1

Sunday, February 13, 2022

More Magic from Corso Marche

Although there was much to distinguish the 1000 Bialbero GT from the preceding 750 Zagato series in terms of body styling/construction, there were also mechanical innovations reflecting the model’s increased speed capability. These included disc brakes and the adoption of a front-mounted coolant radiator. Also significant was the introduction in ’62 of a five speed gearbox.

Recently advertised/sold Abarth 1000 Bialbero GTs:Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Not Just a Pretty Face

In the years 1965-66, Bob Dylan recorded 3 albums which embody one of the most astonishing streaks of sustained creative brilliance of all time. Bringing it all Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde showcased thirty four tracks, not a single one less than first rate, and, astonishingly, nine are genuinely classifiable as ‘masterpieces.’ Talking about what he was striving to achieve, Dylan said: The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind was on the Blonde on Blonde album. It’s that thin, wild mercury sound. It’s metallic and bright gold, with whatever that conjures up. It brings to me, in a visual aesthetic analogy, the sharp – yet harmoniously integrated – angular forms that are the automobile bodies created in 1970-73 by Marcello Gandini in a mid-‘60s Dylan-like purple patch. Limbering up in 1967-69 with sharp-lined ‘concept’ cars such as the Lamborghini Marzal and the Alfa Romeo Carabo, Gandini’s razor-like shapes appeared on the road as the Lamborghini Jarama, Urraco and Countach, Lancia Stratos HF, FIAT X1/9, Maserati Khamsin and Ferrari/Dino 308 GT4. This substantial cadre of cars, with a shared visual mood, represents the very best of early Seventies style, except . . . there was one more such contemporary model that was not envisaged on Gandini’s drawing board. Theoretically, perhaps, it could have taken shape on one nearby Gandini’s, since it is comprised to a considerable extent of the angular lines and forms he himself constructed so successfully. And, somehow, its creator had also been able to incorporate – at a hinted, subtle level – some curvilinear elements that contributed to a balance of supreme litheness at the front end with a muscular heft characterising the rear quarters. This hybrid theme extends to the product ‘package’ – Italian coachbuilding/American power unit; to marque ownership – Argentinian/Italian, and to styling authorship: Tom Tjaarda, an American, (whose father was Dutch-born), based at Carrozzeria Ghia in Turin.

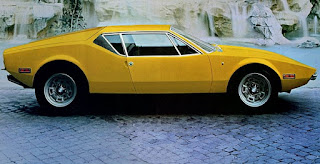

Alejandro de Tomaso founded his marque in Modena in 1959. When his focus turned from his initial interest in racing cars to sports cars for the road, De Tomaso embarked on the production of a series of GTs, culminating in the Guarà, made from 1993 to 2004, (at which date the company failed). The Pantera model preceded the Guara, with a production run begun in 1971, of some 7,000 units. A conventional monocoque, the Pantera was powered by a Ford 5.8 litre V8 coupled to a ZF transaxle. Performance was quoted as 0-60 mph in 5.5 secs and a top speed of 159 mph. Successive iterations included a GTS model with higher output engine, and a Si version late in the production run.

|

| Early standard De Tomaso Pantera |

The

Pantera was not just eye candy. Ford was

enjoying the glow that its success in motor sport had generated through the

late Sixties. Four consecutive Le Mans

victories, 1966-69 and the dominance in Formula One of the Ford-badged Cosworth

DFV engine had done wonders for image building and marketing. Dearborn management was keen to add to its

new exotic GT’s customer appeal by ensuring that it was highly visible and

achieved success on American race circuits.

As a first step, in early 1972, a Group 3-compliant version was made

available. As such, because it was a

class allowing only very limited modifications, it was really just a mild

upgrading of the GTS variant. Most

significant was an increase in engine power, from 330 bhp for the standard car,

to 345 bhp, achieved with a higher compression ratio, better breathing and

freer exhaust gas flow. Also notable, were

wider wheels, (Campagnolo alloys), 8 inch at the front, 10 inch rear.

|

| Early Group 3 Pantera |

|

The first batch of Group 3 Panteras were built between December 1971 and April 1972. It is commonly given that 34 Group 3 Panteras were manufactured, but former De Tomaso director, Giorgio Montagnani, has been quoted as saying that the number was 36. Further, he recalled that 6 of these were full ‘works’ racecars and 4 rally versions of a similar status. The prototype, chassis #1070, was purchased in March 1972 by Auto Club Roma. This car was raced extensively in Italy throughout the decade, by Auto Club and its subsequent owners, Ital Atlantic Express, and then Marco Curti. Racingsportscars.com records a career of 7 years, with 19 events entered, and 3 class wins. (This tally does not, however, include results for the initial two seasons.) |

|

| #1070 at Magione, 1974 |

The FIA class regulations of the time offered

a greater potential for success in the Group 4 category. This allowed for modifications to aspects of

the car that constituted its weaker aspects: weight, suspension, steering and

braking. The standard engine was not

such a feature, but still was the subject of upgrading, (mainly around gas flow

optimisation), taking output up to around 450 bhp. This increase in power, together with a reduction

of weight by around 300kg, enabled good potential class competitiveness. However, a set-back occurred when

an unexpected revised regulation minimum weight was announced, this being some 150 kg above

that achieved by development work including the use of aluminium in

substitution for steel in major panels, fibreglass wing extensions, plastic

‘glass’ and stripped out interior. A

further issue arose during testing as engine reliability became a concern. This would eventually be addressed by the

adoption of lower compression values. Various

sources indicate that De Tomaso built 14 Group 4 Panteras.

At the La Sarthe event, a Claude Dubois-entered car, chassis #2860, crewed by Jean-Marie Jacquemin/Yves Deprez finished 16th, 2nd in class. Three other Panteras were entered, two for Escuderia Montjuich, the other for Societé Franco-Brittanic, but they were all early retirements with blown cylinder head gaskets.

|

| #2860 at Le Mans, 1972 |

|

#2859 at Nivelles,

1972 In 1973 reliability improved and in June works-entered #2873 won in Euro GT at Imola in the hands of Mike Parkes. This was a particularly satisfying victory for De Tomaso, as Parkes had been hard at work in ’72 developing the Group 4 version of the Pantera. #2873 at Imola, 1973 Two months later another ‘big name’ – Clay Regazzoni – took the same car to victory at the Hockenheim round. #2873 at Hockenheim,

1973 That car certainly earned its keep that season – in October it was a winner once again, this time in the Giro d’Italia with Mario Casoni and Rafaelle Minganti at the wheel. #2873 Giro d’Italia start, 1973 Casoni was apparently fully au-fait with the Pantera by late season, having achieved another first-place, this time in #2872, the previous month at Casale. Other Pantera victories in 1973 included Croix-en-Ternois, by Patrick Metral, and at Varano, by Ugo Locatelli. 1974

saw a substantial number of race entries for Panteras. Odoardo Govoni scored 3 victories in the

Spring at Magione and (twice) at Varano.

A repeat win in the Giro d’Italia was missed, but Govoni and Vincenzo

Angelelli's was the best placed of 7 Panteras entered, finishing 3rd. Four cars ran in the Targa Florio, that of

Alex Pesenti-Rossi and Alvaro Valtellina being the highest finisher, in 13th. At Le Mans, Wicky Racing Team intended to run

two cars, but only that of Max Cohen-Olivar and Philippe Carron started, and

was out early with timing gear failure. Wicky Racing Team at

Le Mans, 1974 Once again, in 1975,

Panteras covered a great many racing miles, but no victories are on

record. Govoni was again a prominent

exponent at the wheel, and he was the most successful driver, scoring 2nd

places at both the September and November GT events at the Magione

circuit. Partnering Ruggero Parpinelli,

he also finished 8th, (and 5th in class), at the Targa Florio. Four cars ran at Le Mans, but only the early

chassis, #2860, still run by Team Claude Dubois and now driven by Pierre Rubens

and Paolo Bozzetto, made it to the finish, in 16th place, (8th in class), just

as it had done in ’72. #2860

at Le Mans, 1975 No less than 10 Panteras were entered for the Giro d’Italia, with the Jolly Club car, driven by Bozzetto and Marco Martinenghi taking 5th place, (3rd in class). Highlights of the 1976 season were victories for Pierre Rubens (Team Willeme) at both Zolder and Colmar-Berg, four other podium positions in Europe, and three in Australia. Although there was a greatly reduced participation at Le Mans and the Targa Florio, seven Panteras ran in the Giro d’Italia, with Govoni and Valentino Balboni finishing 6th. #2873 Giro d’Italia,

1976 In the early stages of the 1977 season, Rene Tricot, (Team Willeme), took three victories in Belgium, while in November, Maurizio Micangeli and Carlo Pietromarchi scored a significant win in the Group 4/5 event at Vallelunga. Four cars took part in the Giro d’Italia, Pietromarchi and Giancarlo Naddeo coming 3rd. Carlo Pietromarchi/Giancarlo

Naddeo, Giro d’Italia, 1977 For

the remainder of the Seventies, Panteras continued to feature in numbers in

national/European series racing, but results were mediocre, with just the

occasional win/podium finish. During the

Eighties, participation fell to lower levels, with the cars being considerably

less competitive. This trend persisted

in the Nineties, except that in 1995 Thorkild Thyrring was a major force for

ADA Engineering in the British GT series, winning the GT1 class championship. Thorkild

Thyrring, British GT, Silverstone, 1995 Today

– and in recent times – Panteras are to be seen competing with verve in

Historic meetings. Excellent

video is available of the Group 4 example of Luigi Moreschi on the 2018

Vernasca Silver Flag event. To enjoy the

sight and sound of a Group 3 car running at Spa recently, have a look at this video. A Group 4 Pantera, #2598, is currently

offered for sale, having been competing with considerable success in Romania. #2598, racing in Romania You may have wondered why I opened this piece with an encomium to Marcello Gandini in relation to a car actually styled by rival, Tom Tjaarda. Much as I admire Gandini’s work, I’m sorry to say that I think he despoiled Tjaarda’s masterpiece: In 1989, Alejandro de Tomaso insisted that the job of facelifting the Pantera for 1990 be awarded to Gandini’s consultancy. What resulted was the Si. The main focus of the exercise was on the

front end. A ‘heavier,’ more curvy,

character was conferred by redesigned/rescaled front wings and bumper. The effect on the car’s overall form and

stance was a loss of the pleasing balanced contrast between a svelte front and

a burly centre/rear section. To some

eyes this may have resulted in a more consistent, cohesive design, but, as

such, the Pantera’s body was no longer a physical analogy of its hybrid nature

– Latin style and dynamic flair combined with American motive heft.

I have derived much information from the excellent www.racingsportscars.com. This is an invaluable source of data for anyone researching motor sport history. For the De Tomaso Pantera, refer here: https://www.racingsportscars.com/type/archive/De%20Tomaso/Pantera.html Other essential resources are: http://www.detomasoregistry.org/

http://panterainternational.org/detomaso_history/europes_pantera.html

|

Thursday, January 6, 2022

When 34 bhp Wasn't Enough!

Monday, December 20, 2021

Was the Six in Group 6 Taken Too Literally?

Saturday, December 18, 2021

A Bit of Scorpion Worship - Abarth-Simca 1300 GT

Abarth’s success in creating a small GT car

with big motor sport potential was fully consolidated by the end of the 1950s. The Fiat 600 had provided an excellent

chassis/mechanical basis, and with a lightweight body by Zagato, the 750 GT had

been a winner since its 1956 launch.

Aesthetically characterised in its early form by the double-bubble roof

and ‘matching’ twin hump engine cover, (to optimise delivery of cooling air to

the bay), the 750 became an icon of the era.

By sports/GT industry sector standards, a substantial number of cars

was built, (500-600 units), through to 1960.

Over time, various engine options were introduced: 500, in ‘57/’58, 750

Bialbero, (twin cam), from ’58, subsequently, 700 and 850 versions, and,

eventually, a 1 litre, both single cam and Bialbero. In 1959, Abarth showed its ability with

another ‘base,’ this time the Porsche 356, creating the Carrera GTL. So, when Fiat’s collaborative association

with Simca was made closer at the beginning of the new decade, Abarth was well

placed to use the French marque’s 1000 model as a chassis platform for another

lightweight, competition-suited coupe.

It featured a new 123 bhp, 1288cc 4 cylinder, twin cam engine, (code: F.B.

1300-230), and this was good enough, given the car’s mere 630 kg kerb weight,

to allow a 0-60 mph time of around 6 seconds and a top speed of over 140 mph. A Simca 4 speed gearbox was utilised. This unit was not really adequate given the

power/torque of the engine and was superseded in the final year of production

by a Fiat 850-derived unit. At the same

time, a new engine block, under-bored and with a very short stroke, as used in

the 2.0 litre version, was introduced.

(1600 and 2000 versions of the car became available in 1963-4 in

response to revisions of the capacity limits prescribed by the FIA for the GT

racing classes.) This engine provided a

useful increase in power, to 138 bhp.

|

Engine installation (#0091 ex- Guikas Collection) |

Most cars left the factory with either red or

light blue paintwork, though some cars in period racing photographs, (and some

contemporary survivors), are seen finished in yellow, e.g., #0067 at Le Mans in

1962. U.S. Abarth authority, Les Burd,

also cites photographs of the factory interior in which other colours are to be

seen. There was considerable variation

of bodywork details at a granular level during the production run and,

throughout, there was a basic differentiation between racing, (Corsa), and

street (Stradale), versions. My

understanding is that three substantial iterations are notable: 1) As

originally presented, the engine cover was similar to that of the 1000 GT

Bialbero, though that featured 18 cooling vents, whereas the 1300 had 30. At the front of the car the fuel

tank/radiator bay was covered by a conventional hinged, flat bonnet panel. The transverse front panel had a small

central air intake aperture; 2) With a revised engine cover incorporating a

‘ducktail’ spoiler, lacking multiple vents, but shaped to allow a single large

transverse opening for cooling purposes between its lower rear edge and the

rear panel. Perhaps only on the Corsa

version, some cars feature a pair of brake cooling intake ducts in the front

panel below the headlamps. Between these, a central, rectangular, lower intake for the oil cooler is seen on some Corsa

examples. Some examples of this version

also had ‘c’ pillar air intake scoops, which Cosentino* attributes to ignition

cooling requirements; 3) Referred to as a ‘long nose,’ and as built by Sibona

& Basano. This features a front

clamshell in fibreglass and is readily identifiable by twin external release

handles (as used on the British Triumph Herald), and a full width frontal

aperture. However, with the lack of

documentation available today there can be no certainty about the dates of such

modifications, and it is most likely that there were multiple running changes

and subtle variations in addition to those just mentioned. Furthermore, a neat classification of

versions is made less viable by the fact that when the original batch of 1300

bodies was exhausted, the version developed for the 1600/2000 models was

utilised. These cars featured an engine

cover bulge which was required to accommodate the bulkier greater capacity

power units. Abarth expert, Amedeo

Gnutti, has told me that after the first 1300 model bodies were built at

Beccaris, both that carrozziere and Sibona & Basano were making ducktail

versions, (with the original front ‘short nose’), in 1964-5. Amedeo refers to a few interim types by

Sibona & Basano in 1964 which had revisions to the lower part of the nose,

(to promote downforce), anticipating the ‘look’ of the 1965 ‘long

nose/clamshell’ solution.

* Abarth Guide, by Alfred Cosentino. Published by Alfred Cosentino Books, USA, 1990. ISBN 10: 0929991117

|

#0091 (Middle Barton Garage) showing front clamshell |

|

| Left: Early front end; Right: ‘Longnose’ clamshell version |

|

| Interior (#0091 ex- Guikas Collection) |

The car was presented at the Geneva Show in March 1962. Just a month later three works-entered cars achieved a 1-2-3 at a French hillclimb, the first of many victories for the 1300 GT. Less successful that first year were the entries to the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Works cars with race numbers 41 and 42 were driven by Roger Delageneste/Jean Rolland and Henri Oreiller/Tommy Spychiger, respectively – both cars failed to finish, with ignition problems. A third car, #0067, run by Équipe National Belge, bearing race number 43, and driven by Claude Dubois/Georges Harris, won the 1300 cc class, finishing 14th overall. FIA-homologated for GT racing in October, only the last race of the International Championship for GT Manufacturers season could be entered. There was a significant result - 9th overall and first in class for future F1 driver and 1970 Le Mans winner, Hans Herrmann, partnered by Mauro Bianchi, at the Paris 1000kms held at Montlhéry. In total, including more minor events, nine class victories were recorded that year.

|

| Delageneste/Rolland, Le Mans, 1962 |

|

Spychiger/Pilette,

Sebring, 1963 |

The engine was uprated in 1964, when twin spark ignition was incorporated and homologated. 134 bhp was claimed for the new version, and this allowed the top speed to increase to 147 mph. At that year’s Sebring 12 Hours another class win was recorded for a 1300 GT, this one driven by Fleming/Linton/James Diaz, with an overall classification of 24th. A second car, entered by Scuderia Bear for William McKelvy/Richard Holquist finished down the field in 34th. In April’s Targa Florio, Pietro Laureati/Secondo Ridolfi scored an excellent class win and came in 17th overall. The following month at the Nurburgring 1000kms, six 1300 GTs were to be seen, with that of Herrmann/Fritz Juttner taking class honours and 16th overall. This event resulted in a class 1-2-3 for the 1300 GT, an outcome repeated at six of the other rounds that year. Indeed, at a second event at the ‘Ring, in September (500kms) Herrmann led home an overall 1-2-3. The final table for the 1300cc division of the championship had Abarth-Simca in first place with 60 points – the runner-up, Triumph, scoring less than half that number.

|

| Herrmann/Juttner, Nurburgring, 1964 |

|

| Schiek/Schmalbach, Nurburgring, 1965 |