Left to right: Ducarouge, Chiti, Pavenello.

In amongst all these unsettling developments, there was a new car to be further tested and improved. The 183T was another Ducarouge/Tollentino design. Also as in ’82, the #22 car would be in the hands of de Cesaris, but his new teammate was Mauro Baldi, who had displaced Bruno Giacomelli in the #23 car. Baldi had shown his ability with the F3 championship win for Euroracing in ’81 and he had accrued a season of F1 experience in ’82 with Arrows. Both drivers were getting acquainted with the 890 engine in testing at the Paul Ricard circuit, Le Castellet, in December ’82. At this point the interim 182T was carrying the new power unit and in addition to running reliably, (de Cesaris covered 510 kms on 15th and 16th December with no significant engine problems), surprised many by also being quick – de Cesaris recording a best lap of 1:43.10. For comparison, Patrick Tambay’s Ferrari 126C2: 1:39.68; Eddie Cheever’s Renault RE30: 1:42.75; Nelson Piquet’s Brabham BT52: 1:41.80, (GP circuit).

| | 182T at Monza, September '82 |

At Le Castellet in January ’83, the 182T was

again boosting confidence in the new team.

Indeed, Autosport reported in its 3rd February issue: ‘Alfa

Romeo continued to dominate testing at Paul Ricard last week.’ De Cesaris’s best had been 1:03.55, with

Baldi quite close on 1:05.25: Arnoux was unable to better 1:05:07 in his

Ferrari. (short circuit times). Ducarouge

subsequently said that he believed an even quicker time would have been

possible had the new SPICA fuel injection system not proven intermittently

problematic.

There was a Press presentation of the 183T on

14th February and some subsequent initial running at the Alfa Romeo

proving ground at Balocco. Given that

the 182T had been performing well at Ricard and its replacement was 30 kgs

lighter, there was an upbeat buzz around the team and the new car, though there

was one reservation in that it had not been possible to carry out any wind

tunnel testing. The cars were in Rio in

time for pre-race testing, beginning 4th March. As at Le Castellet, the pace was good and some

reports indicated that the 183T in de Cesaris’s hands was the fastest car

present. It was certainly a

front-runner, along with, surprisingly, the Toleman TG183 of Derek Warwick.

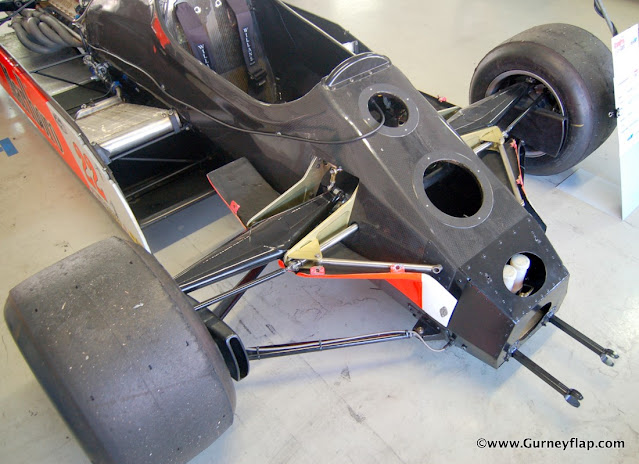

| 183T as presented at Balocco, February '83.

Thus

the Marlboro Alfa Romeo team arrived at Rio, for the Brazilian Grand Prix,

in mid-March ‘83 for the opening round of the World Championship with an

expectation of genuine competitiveness.

However, the stipulation that Italian-made turbos must replace the KKKs had

by then been confirmed by a press release which announced that Avio units would

feature on the 890 engine for the ’83 season.

That this was a decidedly negative development was soon confirmed by the

performance of the cars in practice at the Jacarepaguá track – two laps

appeared to be the maximum they could run before a turbo failure

intervened! If that wasn’t bad enough,

de Cesaris then failed to comply with an instruction to take the car to a

routine weight check. It was a process

newly beefed up to better police compliance with the minimum weight stipulation

of 540 kg. Furthermore, the FIA had made

it clear that disqualification would be invoked if any driver ignored a signal

to pull into the weighing bay. And this

is just what de Cesaris did. As a result,

he was unable to continue to the conclusion of the final qualifying session. So Baldi was carrying considerable

responsibility as the relatively inexperienced sole representative of the Alfa

Romeo marque. He made no friends early

in the race by running into Alboreto’s Tyrrell, (causing its retirement a few

laps later), but did manage good pace, maintaining 6th place in

front of Warwick’s Toleman and Lauda’s McLaren.

But that order was the result of conspicuously blocking driving on

Baldi’s part and when Warwick allowed Lauda past to see if he could get ahead, though

Niki managed that, the Alfa collected the Toleman. Warwick was able to continue, but Baldi was

not, retiring the 183T with suspension damage.

De Cesaris in Brazil, March '83.

Round 2 was the U.S. West Grand

Prix, held at Long Beach at the end of March. This proved to be a curious affair, tyres

being the key for success – those running on Michelins being at a considerable

advantage to the Goodyear-shod competitors.

One such was John Watson and he took his McLaren all the way from 22nd

on the grid to race victory. The Alfas

were also on the French rubber, but it provided them with none of the magic

apparently benefitting Watson. De

Cesaris, who had been on pole and led the race here 12 months previously,

experienced no wonder-comeback from the ignominy of the Brazil disqualification

– in practice he was no better than 19th fastest, (with Baldi 21st),

engine power being again limited by the performance of the Avio turbo units. The car did however keep going until gearbox

problems caused retirement just past half distance. Baldi had been into the wall and out on lap 27.

At this point, Euroracing

showed some initiative and quietly made a deal to purchase four KKK units from

a U.S. Porsche team. The physical

manufacturer identification and individual unit inscriptions were removed and

the turbochargers fitted as replacements for the Avios on both cars, which then

went to Le Castellet for the French Grand Prix. Another improvement introduced at this event

was the incorporation of quick action refuelling fillers similar to a

modification seen on the Renault RE40.

With the refuelling race plan pioneered by Brabham having by now proven the

best way to cover a Grand Prix distance at optimum speed, this was very

welcome, especially taking account of the 890’s prolific thirst for fuel,

(though on race day the team decided to run this race conventionally). Whatever these developments promised in

theory, the reality of de Cesaris’s fastest time in the first day’s practice

was a pleasant surprise. What was not

though was - a French expression

especially relevant here – a déjà vu echo of the Brazil disqualification. That excellent Friday performance was lost

because the time was deleted when de Cesaris’s car was found in scrutineering

to have empty fire extinguishers. Andrea

was half a second slower on the following day, good enough only for 7th

on the grid, while Baldi almost matched that time and took 8th. This encouraging performance of the #23 car

was soon undermined in the race, it being struck from behind by Watson’s

McLaren on lap 1. De Cesaris ran in the

top ten until he pitted with gear selection issues. This lost him 4 laps and though he did run to

the end of the race, he was classified down in 12th place. Baldi again retired after contact with Winkelhock’s

ATS caused him to run off the circuit after 28 laps.

De Cesaris at Le Castellet.

Despite all the positive performance effects

Ducarouge’s contributions had delivered, his 19 months with

Autodelta/Euroracing had seen numerous interpersonal disagreements. Chiti resented the Frenchman’s presence,

seeing him as a threat to his status as the guru on all technical

matters and likely to displace him eventually as the company’s head. Ducarouge, very strong on chassis detailing,

considered that Chiti should confine himself to issues around the powertrain,

though he was not convinced that Carlo’s engines reflected correct contemporary

design principles. Pavenello apparently regarded

Ducarouge’s experience as dangerous for himself, given his own relatively inadequate

technical accomplishments, especially at the sport’s pinnacle. Further conflicts arose over Ducarouge’s

regular demands for increases in budget provisions in order to develop the cars

to higher levels of competitiveness.

Thus the management, from Chiti/Pavenello upwards, saw the Le Castellet

disqualification as an opportunity to attribute blame to Ducarouge and

justification for his immediate dismissal.

This was not only unfair, as really the guilt belonged with the driver,

but also a strategic blunder as Ducarouge’s flair and expertise remained the

team’s best asset in striving for better results. That this was the case was subsequently proven

by what he achieved at the team to which he swiftly moved – Lotus. His ’83 Lotus 94T began a revival of the

team’s fortunes. Two years later his 97T

took Ayrton Senna to his very first F1 victory and in the season ’85-’87

Ducarouge’s designs scored seven Grand Prix victories.

For the next round, the San Marino Grand

Prix, at Imola, Avio turbochargers were apparently back on the engines, at

least according to Motor Sport magazine’s Denis Jenkinson, though he

often got things wrong. It’s possible

that what he reported as seeing on the 183Ts as ‘units being made by Alfa

Romeo themselves,’ were the debadged KKKs. But maybe he was right because practice was

conducted around the need for recurring fault diagnoses and rectifications in

order to keep the cars running and with something near power

competitiveness. Actually, the cars were

relatively quick on the first day of practice, placing 6th and 7th. However, on race day, de Cesaris managed to

roll his car during the warm-up session.

Surprisingly, damage was limited and repairs were completed in time for

the race start. This was a particular

focus for the team as it hoped that the 183Ts would be fast-starting and nimble

in the initial stages as they would be less heavy with petrol, refuelling being

planned for introduction at this event. Once

things had settled down, they were pleased to see that their expectations had

not been unrealistic for de Cesaris was running in 5th and by half

distance he was up to 4th. But . . . perhaps refuelling and Alfa Romeo pit

work were not so compatible? De Cesaris

missed his box slot and there was a substantial loss of time. 20 laps later and he was out, with engine

failure. Baldi’s race concluded in

similar fashion.

At the Monaco Grand Prix, Saturday practice

and qualifying was disrupted by rain, so Thursday times determined the grid

order – 7th for de Cesaris, 13th for Baldi. An oil leak developed on de Cesaris’s car during

the warm up session, so the Euroracing pit was far from calm and orderly as the

cars were prepared for the start. Once the

race was underway the rain which had been on and off up to then stopped and as

the track dried many runners were disadvantaged by having started on rain tyres

and wet chassis settings. De Cesaris

retired with gearbox problems after only 13 of the 76 laps, but Baldi at least

managed to finish 6th and take a single World Championship point -

his first for the team.

According to an

ex-Euroracing engineer with whom I have recently been in touch, KKK turbos

remained on the cars for the San Marino and Monaco Grands Prix. His further recollection is that a reversion

to Avios had subsequently been made in time for the cars’ preparation for the

next event. This might be inferred from

the comments made at Spa by both Denis Jenkinson in his Motor Sport

report: ‘new turbines in the turbo compressors continuing to give a

noticeable increase in reliability;’

and Nigel Roebuck in his for Autosport: ‘Alfa Romeo now has

the facility to turn up the boost without problem, claiming that 670 bhp is

available for qualifying, 640 for the race.’ From these remarks it’s reasonable to

conclude that – perhaps under vigorous urging from top management at

Finmeccanica/Alfa Romeo as a response to corporate embarrassment over the

clandestine use of the KKKs – Avio had made a concerted effort to improve the

performance/efficiency of its units.

De Cesaris at Monaco

Disappointing

though Monaco had been for de Cesaris, the showing at Spa for the Belgian

Grand Prix proved to be his and the team’s best of the season. In pre-race testing at the circuit, de

Cesaris had posted the fastest time, and the car’s suitability there was

confirmed in morning practice by again being top of the timings table. After lunch and under official timing, #22

was 3rd fastest, with Baldi’s #23, 12th – a performance

he could probably have bettered but for an engine blow-up. These became the race grid positions when the

Saturday sessions were washed out, rain falling throughout the day. Roebuck observed: : ‘Andrea, disappointed

that pole position had eluded him, was nevertheless delighted with the balance

of his car through the very fast corners, if less enthusiastic about its

agility in the slower ones.’ The

race start was aborted as Marc Surer’s Arrows was stranded. However, in the few moments the front of the

grid thought it was ‘go,’ de Cesaris shot past Prost and Tambay, and into the

lead. Roebuck described the following

events thus (extracts from his full report):

At the second attempt all was well, and

we beheld the extraordinary spectacle of de Cesaris apparently squeezing in the

sides of his Alfa to get between Prost’s Renault and Tambay’s Ferrari. The Italian V8 gets off the line like no

other turbocharged car, and one rather had the impression of a jet, thrust

built up, then brakes released. The Alfa

scythed between the front row cars as if its throttle was jammed open, and it

was good that the gap was wider than it seemed.~~~~~~~~~~ Down to La Source, de

Cesaris was an undisputed leader.~~~~~~~~~~(At the end of lap 1) Andrea,

belying his hard-won reputation, was driving the Alfa beautifully, with

smoothness and precision, the car’s truly awesome horsepower slinging it from

the corners visibly faster than anything else in the race. The new turbocharger units have certainly

improved the car’s competitiveness. But

how much boost was de Cesaris running?

We wondered that.~~~~~~~~~~While #22 charged along in the lead, however,

its sister car was in the pits after only four laps. Alfa Romeo is by far the most secretive team

in Grand Prix racing, and their explanation

(not always given) after the race was that Baldi’s throttle cable had

broken.~~~~~~~~~~After five laps it was clear that no one could live with the

sheer pace of de Cesaris’s leading Alfa.~~~~~~~~~~At six laps de Cesaris had

extended his lead to three seconds.~~~~~~~~~~De Cesaris completed 10 laps,

quarter-distance, with almost five seconds lead over Prost.~~~~~~~~~~(at 19

laps) De Cesaris made his planned pit stop, but the Alfa mechanics made a mess

of it, particularly those changing the left rear tyre. The Alfa had led by seven seconds before its

stop, but it was stationary for 25.33 seconds, 10 seconds above par. Andrea had to start the hard work all over

again.~~~~~~~~~~(lap 24) Prost was left with a 10 second lead over the

hard-charging de Cesaris.~~~~~~~~~~(after 25 laps) The Alfa was missing, and

soon the news came in that de Cesaris had pulled off with engine failure on the

climb to Les Combes. For many laps the

car had been puffing smoke with every gear change, but its pace had been

unaffected. Had it overheated during the

tardy pit stop? No one at Alfa Romeo was

saying, but it was desperately sad for Andrea, who had driven beautifully.

De Cesaris’s, and the team’s, disappointment

was immense, but there was much to take as positive from the weekend, including

fastest lap at 2:07.5, as he chased Prost after the pitstop.

De Cesaris leading at Sps.

In between the Belgian race and the next, the

U.S. Detroit Grand Prix, improvements to the 890’s cylinder heads

and suspension geometry/ride height were finalised. The value of these changes was not

immediately clear in practice/qualifying for the ‘Motor City’ street race, de

Cesaris securing 8th on the grid, Baldi a disappointing 25th.

After causing an aborted start to the

race, de Cesaris’s fortunes then temporarily looked up as he ran in 3rd

in the early stages. However, turbo

trouble set in, and, with reduced boost, he lost places and eventually had to

retire the car on lap 34 shortly after the routine pit stop. The reliability of the turbochargers was once

again a very significant cause for concern.

Next up was the Canadian Grand Prix at

Montreal. The opening practice session

did not provide much in the way of inspiration for the team, de Cesaris’s 183T suffering

a spectacular engine blow up. Later, the

car had a turbo failure and consequent fire, though this at least excused him

from a weight check (!) which had just been called for. In amongst these vicissitudes de Cesaris

qualified 8th but Baldi was all the way down in 26th. In the race de Cesaris maintained 7th

in the opening stages but eventually had to give way to Rosberg’s normally

aspirated Williams after they had had a coming together on lap 11, then fading

further as his 890 V8 was running hot and losing power, leading by lap 42 to

failure and retirement. Baldi was the

last classified finisher in 10th place, 3 laps down on Arnoux’s

winning Ferrari.

With in-race refuelling now

well established as the preferred run plan, a ‘B’ specification 183 had been

developed in time for the British Grand Prix at Silverstone. This featured a monocoque of reduced size to

take advantage of the opportunity to carry a smaller fuel tank. Aerodynamic advantages were also expected as

the chassis/body height was also decreased, allowing a better airflow to the

rear wing surface. In practice, however,

the new cars were found to be no quicker than the original examples had been in

previous test running at the circuit. De

Cesaris was able to qualify his car only 11th and Baldi was 13th. Disappointing as these grid positions were,

what was even more so was that de Cesaris’s time was 2.5 seconds slower than

Arnoux’s pole effort. His and Tambay’s

Ferraris locked out the front row and were clearly dominant. With front-running retirements, de Cesaris

moved up as high as 4th at one stage, but once again was the victim

of a sloppy pit crew which he then compounded by stalling the engine and thus

being delayed enough to drop back to 12th. He recovered to the extent of an 8th

place finish, unusually in this instance, behind Baldi, who was 7th.

Left: 183T; right 183TB ('lowline').

The Ferraris were again the cars to beat at

the next round, the German Grand Prix at Hockenheim. De Cesaris was the closest to doing that in

qualifying, though he was nearly 1.5 seconds off Tambay’s pole time. Baldi managed 7th. The 183Ts seemed to be benefiting from better

engine power derived from further turbo specification upgrades. In the race de Cesaris was initially

displaced by both Brabhams and both Renaults.

In the latter stages, Cheever’s Renault and then Piquet’s BMW failed,

leaving de Cesaris in 2nd, in which position he finished the race,

though at reduced speed on the final lap as the 890 V8 had developed a rather

ominous, abnormal noise. Baldi’s car,

however, was subject to a turbo failure and was retired just after half

distance.

Moving on to the Osterreichring for the Austrian

Grand Prix, the team was in confident mood thanks to de Cesaris’s excellent

result at Hockenheim. This soon

dissipated when de Cesaris’s engine blew up during practice. With much track time lost while the necessary

change was made, Andrea had to see his teammate outqualify him – Baldi was 9th,

de Cesaris, 11th. And, come

race day, de Cesaris might well have felt that the gods were getting-even in

response to his good fortune in Germany.

Firstly, his engine blew up during the warm-up session. And although the team managed to get yet

another installed for the race start, the particular unit was even worse than

normal, fuel consumption-wise. Thus,

when the routine re-fuelling stop had to be delayed because of pit road

congestion, the car ran out of fuel whilst going well in 4th place. Baldi had been out earlier, at just quarter

distance, an engine oil leak being determined as terminal.

Perhaps the frustrations in Austria were the

cause of de Cesaris’s grumpy disposition in practice for the Dutch Grand

Prix at Zandvoort – but, whatever its origins, the on-running disputes he

had with Riccardo Patrese proved a distraction and he and the car were probably

capable of better than the 8th fastest time he eventually recorded. But his engine had also again given trouble,

restricting the number of laps he was able to complete. Baldi was 12th. As for the race, it was an early exit – after

just 5 laps – for de Cesaris, with another engine failure. Baldi, on the other hand, took his car to 5th,

his best result of the season.

Prior to the Italian Grand Prix, tyre

testing at the Monza circuit had seen de Cesaris once again setting the pace in

the 183TB. He continued to do so in

first practice but was able to qualify for the race only in 6th

place after experiencing an engine failure. Baldi had a turbocharger break and could do no

better than10th. Both cars

seemed to be lacking optimum straight line top speed, so important at

Monza. De Cesaris started the race

strongly, lining up on lap 2 to overtake Tambay for 5th, but the

Ferrari forced the Alfa wide and its race was done, stranded in the run-off

area. Baldi’s car was also a very early

retirement, limping into the pits on lap 5 with a badly smoking, failed

turbocharger.

A ’European’

Grand Prix was run at Brands Hatch, England, in late September. In pre-race tyre testing there the 183TB had

displayed notably improved balance and grip.

However, back again for race practice, de Cesaris considered the

driveability of the car less good, both in terms of handling and throttle

response, wastegate revisions having apparently not improved turbo lag. Whether these factors – or just a driving

error – were to blame, de Cesaris had a substantial off on the first day of

practice and after the car’s repair found himself dissatisfied with the

engine’s performance. Trying the spare

car did not prove to be particularly effective as he was unable to qualify

better than 14th and only just a little quicker and one place

forward of Baldi. Finding the car much

more to his liking on race day, de Cesaris worked up the field, and as the

finish approached, he was firmly established in the points-scoring positions,

eventually crossing the line in 4th and thus an encouraging

performance and only his fourth finish of the season to date. Baldi made it only to half-distance before

pulling out with a clutch failure. |

Baldi at Brands Hatch.

The final round of the World Championship –

the South African Grand Prix - was held at Kyalami. De Cesaris and Baldi qualified 9th

and 17th respectively. De

Cesaris made another of his lightning starts, up to 5th by the end

pf lap 1. He maintained good pace

throughout and was 4th until near the end, but then, with Lauda

retiring and Piquet going very cautiously in order to ensure his World Championship

victory, #22 was 2nd at flag fall.

Baldi had retired after just 5 laps with an engine failure.

So the season ended on

something of a high, if not a vertiginous one.

De Cesaris had accumulated 15 points, for 8th place in the

drivers’ World Championship. Baldi’s

total was 3, 16th. Alfa Romeo

stood 6th in the constructors’ World Championship. And that was it. De Cesaris and Baldi were moving on, as was

Marlboro. Riccardo Patrese and Eddie

Cheever, replacing the Italian drivers, proved mediocre at best in the

following season, though they did not have a good car in the 184T, itself a

compromise design as a result of the reduced fuel allowance introduced in the

regulations for ’84. The car, a

development of the 183, was credited to Tollentino, featured a new, very

distinctive Benetton livery, (the team’s new main sponsor), but little else of

note. The 185 was the designation for

the following season, at the end of which Alfa Romeo announced its withdrawal

as a F1 car constructor. As an ending,

this was somewhat less illustrious than that seen in 1951 when the 159 had

retired gracefully as the World Championship-winning car.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment