Especially

notable cars were Bonnier’s Ferguson, Brabham’s Brabham and Muller’s Porsche

‘missing link.’ The Ferguson was a very

distinctive machine, it being not only 4 wheel drive, but also the last car

built for Formula 1 with a front-engined powertrain. In addition to this victory in Switzerland,

the 2.5 litre car was further successful in capturing the 1964 British

Hillclimb Championship. The Brabham BT4

was introduced in 1962, primarily to be raced in the Tasman series ‘down

under.’ Its agility, however, made it very

suitable for hill-climbing and the third (of three) chassis constructed was

sold to Charles Vögele specifically for European hill-climbing campaigns – and

in 1963 he was dominant in the car in the Swiss national championship.

As

I outlined in The Dream Hybrid -

Conceived in the Fifties!, the ‘Dreikantschaber’ was created to bridge the gap

between the Porsche GTL and the 904: Porsche had readily appreciated since

the latter part of 1962 that it would need something more radical than the GTL

if it was to retain its competitiveness in the GT racing classes – threatened

as that would be by new/improved rival models such as the Alfa Romeo TZ and the

Abarth Simca 2000. Thus, while the GTL

would continue through 1963, the 1,966 engine and better brakes began also to

be utilised in a new bodied, 718, RS61-based, ‘GS-GT.’ The two examples of this made – also known as

‘Dreikantantschaber’/DKS* – ran in parallel with the GTLs, from the Targa

Florio onwards. This model would serve

as a steppingstone to the ultimate requirement, a mid-engine GT, which was

realised in November 1963 with the initial presentation of Butzi Porsche’s

rapidly-developed 904/Carrera GTS. *This

is the German name for a sharp, triangular-pointed scraping tool – the visual

reference being to the ‘sharp’ form of the car’s nose/front end.

Both

images below courtesy of Automobile Sport.

Left: Hans Herrmann claiming 3rd in the Abarth Spider Sport;

right: Jo Bonnier with the Ferguson P99.

The

1965 event was the 17th (of 20) round of the World Sportscar

Championship, which that season was two-pronged: 1) International Championship

for GT Manufacturers, and, 2) International Trophy for GT Prototypes. The former, in its Division 1 class, was

dominated and won by Abarth, the marque’s fourth consecutive World Championship

triumph. Ferrari was clearly in the

ascendancy in the Prototypes competition and would finish the season with

almost double the points scored by runner-up, Porsche. Within the European Mountain Championship,

Ludovico Scarfiotti’s scoring had been underlining Ferrari’s strength, with his

Sant Ambroeus-entered, (works-backed), Dino 206 SP being the winning car at

Ollon Villars, as it had been at Trento Bondone, Cesana-Sestrieres and

Fribourg.

Scarfiotti's car was an open-top version of the Dino 166 P with a bigger (2.0 V6) engine, giving

218 bhp. For his part, Scarfiotti was an

extremely accomplished and versatile driver, having won the European Hillclimb

Championship in ’62, Le Mans the following year, and he was an Italian Grand

Prix winner. His main opposition in ’65

came from the works Porsche 904/8s of Gerhard Mitter and Herbert Muller and

Abarth 2000 OT of Hans Herrmann. Also

able to challenge were, for example, 904 GTS Porsches in the hands of drivers

such as Herbert Muller, Rolf Stommelen and Michel Weber, while Herbert Demetz

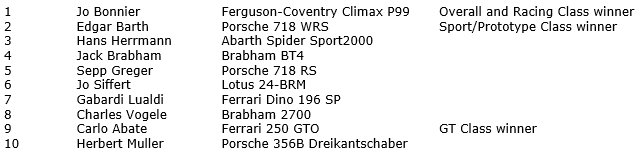

could also turn rapid ascents in the 2.0 Abarth. The ten fastest in ’65 were:

The

model designation of Mitter’s car (chassis #906-010) was enigmatic and quite

confusing. Firstly, though referred to

as 904s, the Bergspyders used for sportscar racing and hill-climbing in ’65 had

chassis numbers configured 906-0xx, all with an eight cylinder engine. To compound potential misunderstandings, #010

was used for a chassis which appeared at the Rossfeld hill-climb meeting in

June but was then promptly junked and the number re-used for the chassis Mitter

debuted at Ollon Villars. This was

itself distinctive as it was an even lighter Bergspyder – at 488 kg – thanks to

a new tubular spaceframe construction, one of the first outcomes of Ferdinand

Piech’s involvement in the works racing organisation. Thus, this car was virtually a 906, a model type

which would long remain emblematic of Piech’s influence and achievements. Crucially, the 906 allowed a huge scope for

development, in contrast to the limitations of the 904, being more of a road

car modified for the track.

Alongside

Mitter’s 904/8 as a Porsche System Engineering Ltd. (i.e. works) entry, was an

Elva Mk.7, driven by Anton Fischhaber.

This was powered by the same Type 771 1,991 cc flat 8 engine used in

#906-010. The Elva chassis, as proven in

other applications, was effective and enabled Fischhaber to finish 16th,

his best time being 4 min. 36.3 sec, 24 seconds greater than Mitter’s. For further comparison, the similar, but BMW

M10-engined Mk.8 Elva of Sidney Charpilloz was 5.4 seconds slower.

With

his World Championship successes of the era, Carlo Abarth was keen to add the European

Mountain title to the brand’s the honours list.

His problem however was the lack of a multi-cylinder engine of the level

of capability at the disposal of the

Porsche and Ferrari marques. Of the

several coupe and barchetta type cars being built at Corso Marche mid-decade,

the most suitable for the hills were the OT (Omologata Turismo) Spiders. There was however an underlying compromise in

so much as the Fiat 850-based chassis was relatively heavy. A positive feature however was the first use

by Abarth of glass fibre for fabrication of the whole body structure. Designated as Tipo 139, the car, as driven at

Ollon Villars by Demetz, utilised the 1,946 cc version of the Abarth 4 cylinder

Bialbero, good for 209 bhp. In simple

terms the Abarth’s main disadvantage against the Porsche and the Ferrari was

its weight – quoted as 710 kg. Thus, it

was bound to struggle with performance, given that its 209 bhp compared with

218 for the Ferrari and at least 250 from the Porsche unit.

Images

below, left: Peter Ettmuller’s Shelby Cobra, finished 19th; centre: winner,

Scarfiotti’s Ferrari 206P. (Copyright GPL – Geoff Goddard); right: Ferrari 275

of Giampiero Biscaldi. (Courtesy Alamy).

The

meeting in 1967 – also known as the Swiss Mountain Grand Prix - was the

last which enjoyed the status of being a round of the International

Manufacturers Championship, (also known previously as the World Sportscar

Championship, and, subsequently as the International Championship for

Makes.) The change of status was no

reflection on the venue – hill-climbing underwent a diminution of popularity

through the sixties, and events became less well supported. While there were four climbs in the 1965

Championship calendar, Ollon Villars was the only one in ‘67, and the category

did not feature anywhere in subsequent years.

The European Hillclimb Championship would however continue, (through to

the current day), and in ‘67 Ollon Villars was the penultimate of eight rounds. The competitors arrived at the Vaud canton in

late August, with Porsche assured of the Championship, its cars, running in the

premier, Sportscar (Prototype), class, having been victorious at all six of the

previous rounds.

The

two Weissach works drivers were Gerhard Mitter and Rolf Stommelen. Mitter was the reigning European champion

having outscored the opposition in 1966 at the wheel of a Porsche 910 coupe. The Porsche System Engineering team was keen

to repeat that success and was conscious that an increased level of competition

could be expected in ’67, especially in the shape of the Abarth 2000 SP, Ferrari

412P, Lola-BMW T110 and Alfa 33. Thus it

was decided to revert to the ultra-lightweight Bergspyder format as had been

successful in ’65 (904/8). This decision

was facilitated by a regulations change which removed the minimum weight limit

and reintroduced governance by the very liberal Group 7 technical stipulations. Both using the resulting 910/8 Bergspyder,

Mitter and Stommelen had won all the previous rounds, at Montseny/Trento-Bondone/Freiburg-Schauninsland

and at Rossfeld/Mont Ventoux/Cesana-Sestriere, respectively.

Key

specification features of the Spyders included the very low weight of just 499

kg at the beginning of the season. And

this was further reduced as development continued during the season, primarily

on the car allocated to Mitter, the frame of which was rebuilt in aluminium, a

measure that gave a one-third weight saving.

A variety of other modifications included a tiny fuel tank – 15 litres

capacity – and some exotic materials: magnesium wheel rims, beryllium for the

brake discs and titanium for the brake calipers and stub axles. Bodywork was in very thin gauge glass-fibre with

notably short side panels – prompting a ‘Mini-Skirt Spyder’ nickname. By the time of the Ollon Villars event, the kerb

weight was down to 418 kg. A side

benefit of the enhanced light weight was the feasibility of using ballast over

the front axle in order to ‘calm’ the handling characteristics, contributing

significantly to the car’s drivability. As

for the other crucial performance component, the type 771 engine delivered 260

bhp. All this was good enough to allow

Mitter to take first place with a time of 3 min. 55 sec, (for comparison, the

eventual record time, achieved by Francois Cevert in ’71, being 3.47). The top ten in ’67 were:

The

Ollon Villars course was not generally thought to be especially hazardous,

though following his outright record-establishing run in ’71, Francois Cevert

is quoted as saying: ‘Never again will I indulge in such a dangerous adventure.

I find the climb quite frightening, brushing guardrails at high speed and

clipping trees. Circuit racing is much less demanding.’ Cevert’s opinion is validated by the fact

that two drivers died at the ’67 event – Axel Perrenoud, driving a Shelby Cobra

on the Friday, and Michel Pillet the following day at the wheel of a Ecurie La

Meute Triumph Spitfire.

Images below, left: Peter

Schetty’s Abarth 2000 SP, 4th fastest. (Courtesy Equipe Bergamote);

centre: Sepp Greger’s Porsche 906. (Courtesy Zwischengas CZ); Porsche 910 of

Rolf Stommelen. (Courtesy Karl Ludvisgen).

On

31st August 1969 the 7th round of the European Championship

was again held at Ollon Villars. Where

’67 had been a season of Porsche and Mitter/Stommelen domination, ’69 had

proved to be a walkover for Ferrari and Peter Schetty. He had mastered the 212E Group 7 barchetta

and was very fast on all the ‘mountain’ courses. In winning once again at Ollon Villars –

making it a championship series clean sweep, (though he was not entered for the

final round at Gaisberg) – Schetty set a fastest time of 3 min.47 sec, 8

seconds better than Mitter had managed in ’67 and a fraction slower than

Cevert’s all time record. The 212E was a

development of the Dino 206S with various weight-saving modifications similar

to those practised by Porsche on the Bergspyders. But, as implemented at Maranello, such measures

did not result in an equally lightweight car, the 212E weighing in at around

515 kg. The Ferrari however benefited

from a very high performance engine (Tipo 232) – a 2,000 cc flat 12 rated at

over 300 bhp.

Images

below; left: Schetty, Ferrari 212E, 1st place. (Courtesy

SupercarNostalgia); centre: Alfa Romeo 33/2 as raced by Michel Weber to 5th

place, (this photograph not taken at Ollon Villars); right: Arturo Merzario in

the Abarth SE010.

The

FIA-governed European Hillclimb Championship has continued through to the

current day. Since the last Ollon

Villars-hosted round in 1971, various revival events have been held there, the

first being in 1998 when 12,000 spectators attended the International

Retrospective Hill-Climb.