Young,

single minded, supremely confident and abrasive – such a character often makes waves

but is usually defeated by the authority and inertia possessed of an elder

generation of management. But Ferdinand Piëch

was a bit different. Joining the ‘family

firm’ – Porsche – in 1963, Piëch was already in charge of testing in 1966 at

the age of 24. As the son of Ferry

Porsche’s sister, Louise, some may have thought there was a touch of nepotism

about this – but Piëch would rapidly show that it

was actually all about his ability and character.

|

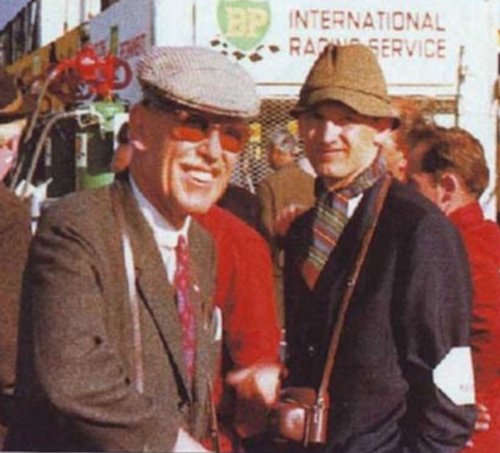

| Piëch (right) at the 1965 Targa Florio with Fritz Huschke |

Piëch

soon became deeply involved in the creation and evolution of the Group 4/6

Porsche 906. This was a ground-breaking project

for Porsche as the car embodied the adoption of key, pure-race features,

primarily, 200+ bhp, lightweight 6 cylinder engine, glass fibre body, super-light

tubular space frame chassis and high focus on aerodynamics, (the 906 was the

first Porsche wind tunnel-tested), with emphasis on lowest possible coefficient

of drag. The car was an immediate,

class-winning success. This was

instrumental in reinforcing Piëch’s firm belief in the primary importance of

vehicle top speed, based on lightness of construction and an exceptionally low

Cd metric. Several of his colleagues

have said that this went beyond ‘firm belief’ into the realms of unshakable dogma.

|

| Porsche

team with Piëch, centre, on return from 906’s

winning debut at Daytona |

In

its first season, the 906 scored class victories in the major sports car races

at Daytona, Sebring, Monza, Targa Florio, Spa, Nurburgring, Le Mans, Watkins

Glen, Mugello, Zeltweg and Montlhéry. It

was successful too in the following two seasons. And while all this convinced Piëch that his

technical ‘recipe’ was unchallengeable, Ferry Porsche became certain that a

racing project of the utmost importance could be entrusted to his dynamic young

nephew. Meanwhile, certainty was a state

of mind difficult to find amongst the senior officials at the Fédération

Internationale de l'Automobile. It had

felt some alarm that the topflight sports car racing it administered had seen an

incursion of entries involving cars equipped with large capacity production

stock-based American V8 engines. Ford

had led this trend with the introduction of the GT40, initially utilising 4.2

and 4.7, and, subsequently, 7.0 litre engines.

Once an American victory at Le Mans had been achieved in 1966, the FIA

became concerned that the European makers such as Ferrari, Porsche, Maserati,

etc, would be deterred from future competition.

So, in reviewing its technical rules, it sought to redefine Groups 4 and

6 in the favour of European-taste products, primarily by imposing engine

capacity limits of a 3000 cc and 5000 cc respectively.

For

Porsche too, the second half of the decade looked likely to be hugely

significant. Like Ford, it was eager to

have its status as a premium marque confirmed by racing success at World

Championship level. And, as had been the

view at Dearborn, an outright victory at Le Mans was seen at Zuffenhausen as a prize of

inestimable value. Ferry, his careful,

conservative nature to the fore, blanched at the prospect of needing to build a

5.0 litre car to achieve this. In every which way he contemplated the costs that would be involved – made all the worse

by the homologation requirement to build 50 examples – he struggled to find the

courage to make the commitment, fearing that even if successful in sporting

terms, the project could bankrupt the company of which he was so proud. But the pro-build lobbying of Piëch was

suddenly given added persuasiveness when the FIA announced in April 1968 that

the number of cars required for homologation would be reduced to 25. Within two months the Porsche board had

agreed a go-ahead for the 917 project and in the July Mezger’s team began work

on designing the type 912 flat 12 engine.

|

| Original 917 Longtail with front tabs and rear flaps/spoiler |

Meanwhile,

though the 907 was enabling several drivers to become used to being class

victors, it was also bringing them regular moments of extreme concern. For, whilst they enjoyed the availability of

top speeds in the order of 190 mph, at such pace the car was notorious for its

instability stemming from its ultra lightweight chassis and low drag/downforce

body, the very features that enabled the speed.

For Le Mans and Daytona, the 907 ran with a longtail body, but this gave

no better drivability characteristics than the short-tail version. As the 1968 season dawned, the 907 ‘became’

the 908, with initial concentration on a longtail variant. This proved just as liable to wander at high

speed at the Le Mans test event. Trim

tabs and spoilers were found to have little beneficial effect, but the addition

of two turbulence-constraining fins on the tail did. The following year it was the new 917 which

was in La Sarthe in June, and, as might have been expected, they tended to need

the full width of the straight while carrying their even greater maximum speed

of around 215 mph. This remained a

characteristic of the 917 through its maiden season despite the rear body

movable flaps which had been a design feature from the outset. This issue and how it was addressed is the

main subject of this article, we’ll come back to it later.

|

| Piëch (right) with Gerhard Mitter at the public debut of the 917 at Geneva, March 1969 |

Piëch

at the FIA homologation inspection, April 1969

The

closing two decades of the twentieth century saw an increasing tendency for

cars to be ‘designed by committee.’ For

consumers of an enthusiast bent there grew a feeling that the products they

were being offered lacked distinctive character, failed to be individually

innovative and were more and more generically formulaic. This contrasted with what had made the

sixties and seventies so much more rewarding – an industry which allowed

outstanding individuals to create vehicles brimming with their own personal

creative DNA – stylists such as Giorgetto Giugiaro, Marcello Gandini and Tom Tjaarda,

engineers like Sir Alec Issigonis, Giotto Bizzarrini and Rudolf Hruska. To that second list we could add Ferdinand Piëch. Of particular interest here, his creation of

the Audi A2 is worthy of some consideration.

Although the model’s design is credited to Luc Donckerwolke, he

specified and visualised the vehicle in compliance with the very detailed brief

dictated by Piëch. Key features, with ultra-high

fuel use efficiency as an overriding objective in mind, were: aluminium

body/chassis construction; optimum interior space utilisation/minimum external

footprint and frontal area; small capacity/high efficiency petrol and diesel

engines. It is likely that progress of

the concept through to volume production would have been halted at any factory

other than Audi’s at that time since the use of aluminium significantly

complicated and added cost to the build process. What got the A2 through to dealer showrooms

for its 1999 launch was Piëch’s force of personality and belief that he knew

better than anyone what customers really wanted in a contemporary small car. That Piëch was an exceptional ‘force of

nature’ is recognised for instance by the existence of academic studies

analysing his psychological make-up, most notably the Frontiers in Psychology

paper, Ferdinand Karl Piëch: A Psychobiography of a Ruthless Manager and

Ingenious Engineer, by Claude-Helene Mayer, Roelf van Niekerk and Nicola

Wannenburg, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8490634/

However,

five years later I was making presentations at Audi UK regional dealer meetings

and witnessed a personal ‘first.’ I had

previously attended many such meetings for the BMW, Alfa Romeo, Chrysler and

Lotus marques and had frequently enjoyed seeing the attenders expressing

enthusiasm for a new model/version announced at the event. But in 2004, I was just a little taken aback

by similar glee being forthcoming, but, and this for the first time in my

experience, in response to confirmation of rumours that a model was to be

canned. Yes, that was the A2, a car that

despite many good attributes was not liked at all by most Audi dealers. For them, it didn’t ‘fit’ – the brand was

building a ‘family’ of models which shared DNA associated with aggressive

style, performance and ‘street presence.’

The A2 didn’t even hint at any of that, but, worst of all, it was seen

as too expensive for its natural market sector.

All that aluminium and the specific build processes involved made that

inevitable. Piëch was credited with

great vision in identifying a car of the future but berated for persisting with

the concept and being responsible for consequent and considerable financial

losses. Nevertheless, it is likely that Piëch

himself never accepted that his concept was incorrect for the particular

context – it would be the customers and the dealers who hadn’t a clue. Recognising that attitude of mind now helps

us understand just what happened at Zeltweg in mid-October 1969.

The

commonly quoted anecdote is that senior engineer, John Horsman, of JW

Automotive, (the Gulf-sponsored team that would spearhead the Porsche World

Championship campaign in 1970), noticed something missed by the factory

engineers, Peter Falk and Helmut Flegl. Brian

Redman and Kurt Ahrens Jnr. flogged round the Osterreichring circuit for the

best part of two days, failing to achieve the target lap time by a margin of

1.5 seconds. Then, according to the

‘legend,’ it dawned on Horsman that whilst most of the bodywork of the two test

cars was peppered with insect corpses, the rear bodywork surfaces remained

clean and perfectly inoffensive to any entomological specimens minding their

own business whilst making their way down the pitlane.

Two

aspects of this missing midges mystery may have been misunderstood by certain

parties and at certain times in the past.

Firstly, several writers, contemporarily and in more recent times, have

concluded that those clean top surfaces indicated that no airflow was attaching

there, robbing that part of the car of a downforce pressure influence. However with today’s ever greater

understanding of aerodynamics, a more likely reading is of a rear body shape

that attracted and conducted an airflow with potential to exert downforce but

which also tended to allow turbulence from the sides to spill over and undermine

that downforce. What is more important,

of course, is that Horsman set JWA’s Ermanno Cuoghi and Peter Davies to the

task of fabricating there and then a ramp-like cover which provided a new,

raking rear section which anticipated the 1970 Kurz version of the car. Though they were unable to get the work finished

that day, the modified car was ready for Brian Redman to try again the

following morning. And how good do we

think did Redman – and the engineers – feel when his immediate reaction was

that the car was transformed and actually enjoyable to drive!

Misunderstanding

2: John Horsman was undoubtably an excellent engineer with a lifetime of

achievement and a career marked by association with some of the most

prestigious marques – Aston Martin in the 50s/60s; Ford Advanced Vehicles for

the 60s Le Mans victories; JWE/Porsche; Gulf Research Racing with the Mirage

model in the mid-70s. However, it is

most unlikely that it was only John who noticed the absent arthropods. Falk and Flegl surely observed the same phenomenon

but were quite possibly reticent for good reason. That body shape, evidencing its aerodynamic

flaw such as it was, was also demonstrating its supremacy in the low drag

stakes. To disturb that with revised

rear panel sections, spoilers and flaps would surely be an act of sacrilege in

the view of the man who had specified this automotive holy grail – Ferdinand Piëch. And with

their responsibilities within the 917 project, the last thing that Falk and

Flegl really ought to be doing was challenging a basic tenet of the Piëch

philosophy. Thus they were perhaps being

understandably self-protective when they 'did a Nelson' and didn’t mention the

lack of gnats – safer to leave that to John!

Happily

for Porsche, engineering niceties stood back, there was no overt challenge to Ferdinand’s

principles – to his face at least - and the Zeltweg solution snuck through. On the second day of the tests, Ahrens’s best

lap had been 1.48.2, whereas he eventually got down to 1.43.2 before everything

was packed up for return to Stuttgart. In

Karl Ludvigsen’s account of the tests, (in Porsche: Excellence was Expected,

Book 2), he records that a management contingent including Piëch arrived at the

circuit the next day. Horsman apparently

recalled, “. . . the group ignored our presence as though we were hired day labourers

and departed without speaking to us! Oh

my, I thought, what have we gotten ourselves into.” Ludvigsen’s narrative continues:

All too soon he (Horsman) would learn of the rival Piëch-backed Salzburg team. When John Wyer and Ferdinand Piëch met later, the Austrian smiled wryly and said, “It seems that your tail is three seconds faster than ours. So that is what we must do.” It was a solution that came from all of us,” summed up Peter Falk. “Later Mr. Wyer and Mr. Horsman said it was their work. And we naturally told Mr. Piëch that it was our work.

No comments:

Post a Comment